Yes, we’re still sailing… but they’re blowing snow on the mountains while those who’ve learned how to sail this season wonder when to switch gears!

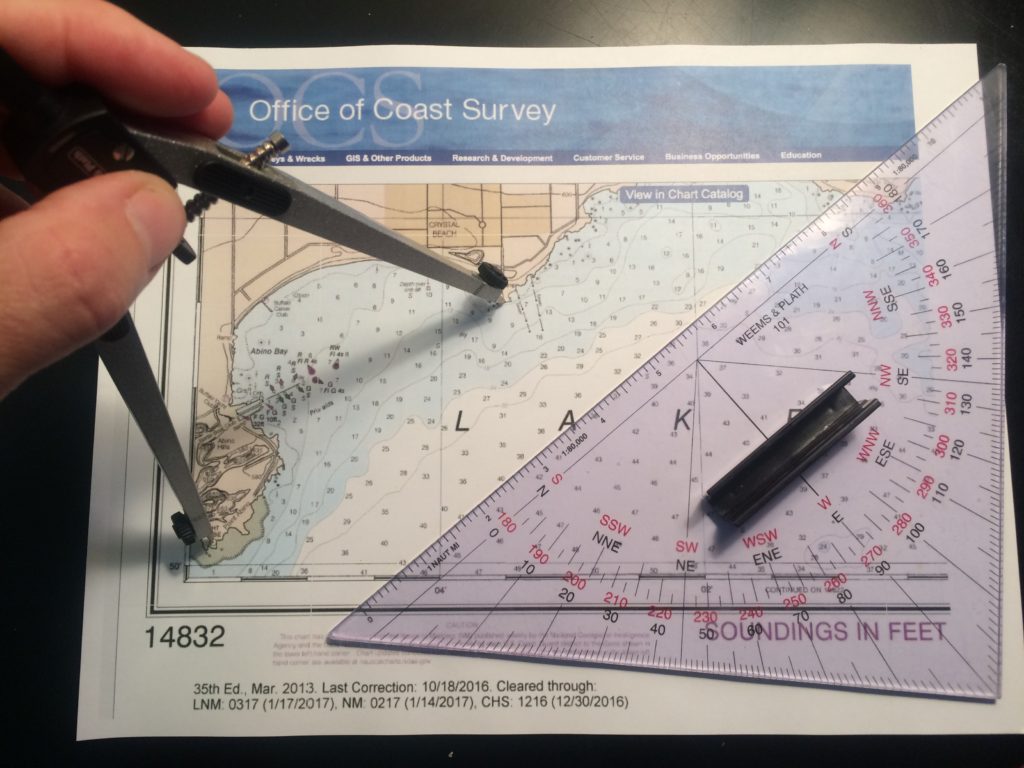

Soon we’ll be switching gears – Live 105 Coastal Navigation courses (both in person and on Zoom), and our Virgin Islands (BVI) trips for sailing vacay courses. And, snowsports!

Each fall and spring, people who sail and also ski or ride sometimes have a choice to make: slide through water, or slide on snow. That time is just about here in the northeast. Killington began making snow awhile ago, and while not open yet, it’s probably just around the corner. They often start with a few trails in late October, and host a world cup women’s ski comp each Thanksgiving weekend.

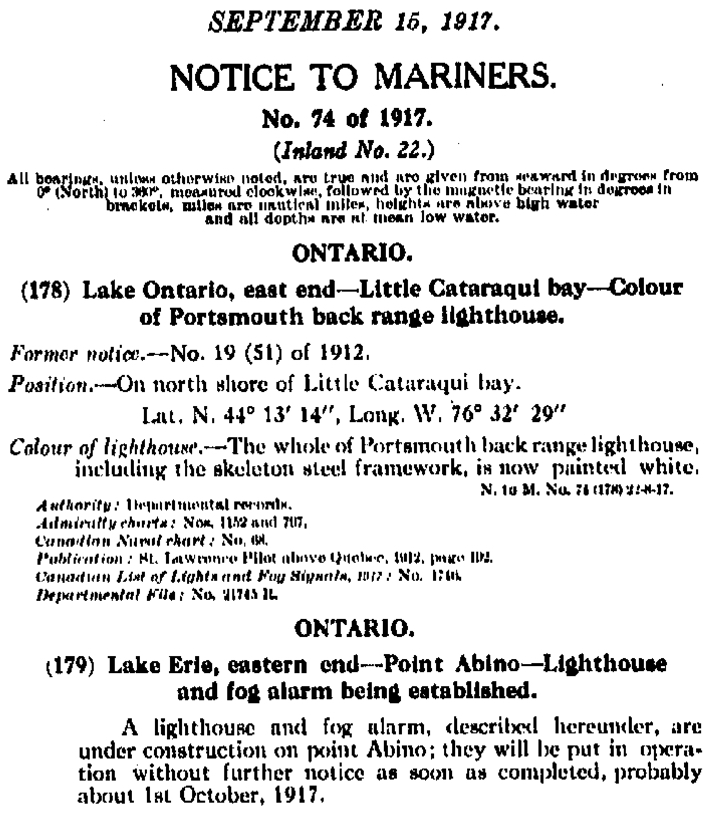

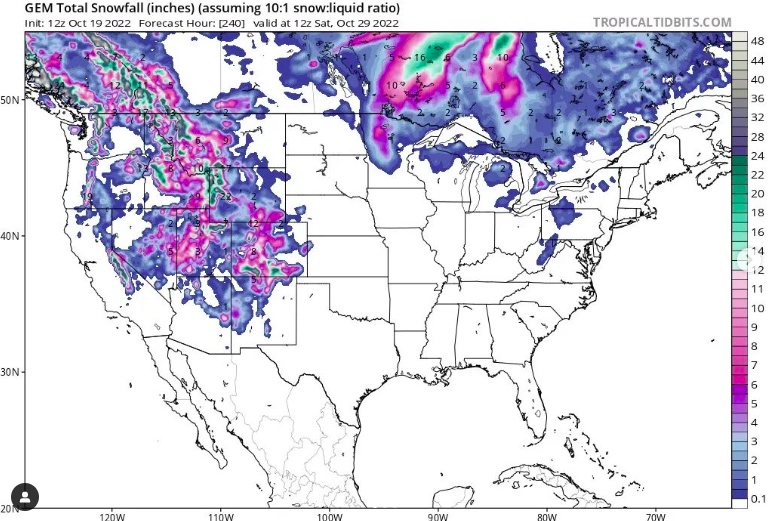

And, there was a dump in the midwest already! Michigan got it, and they’re already doing it. Much more is coming out west shortly – as in a few days.

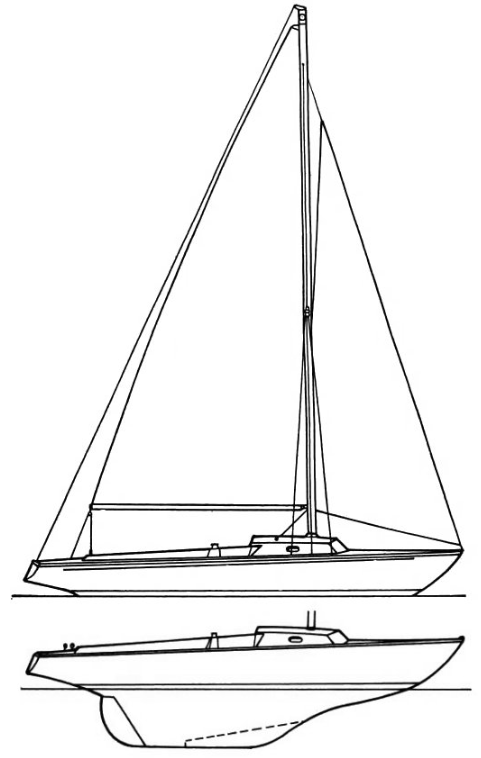

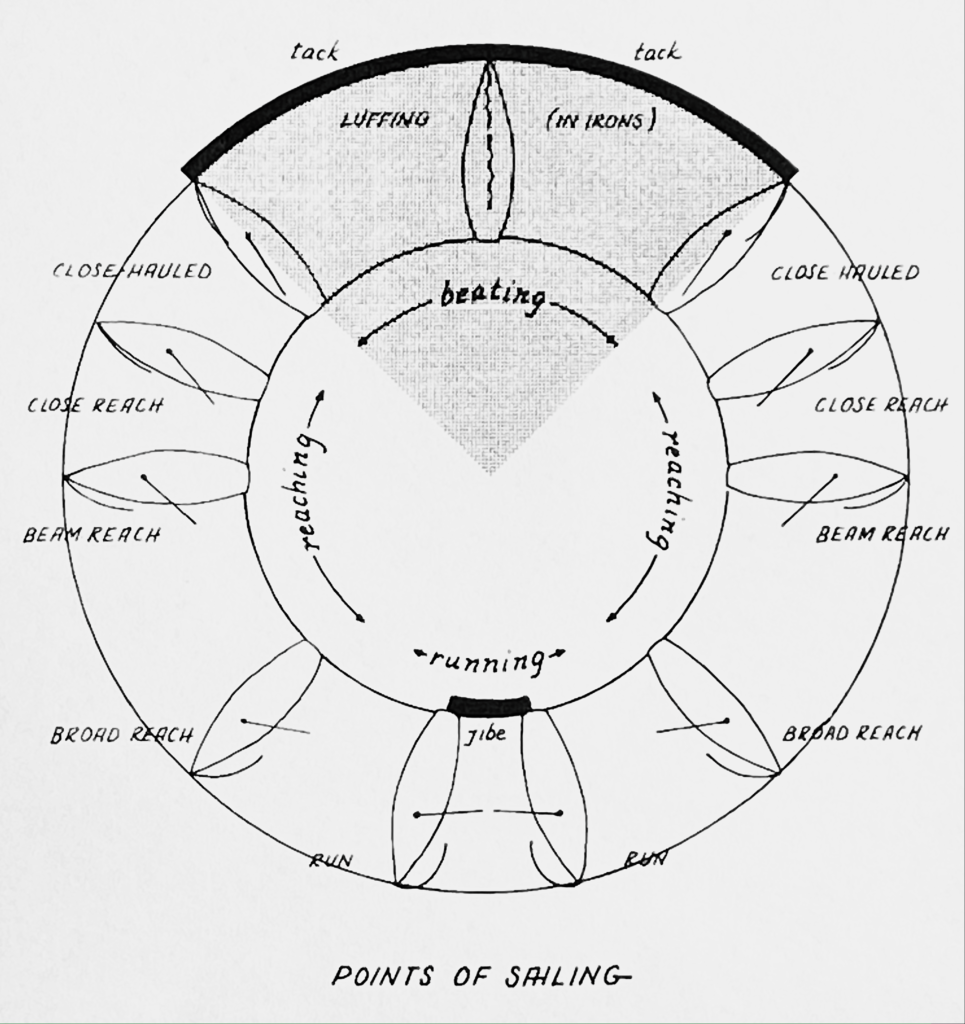

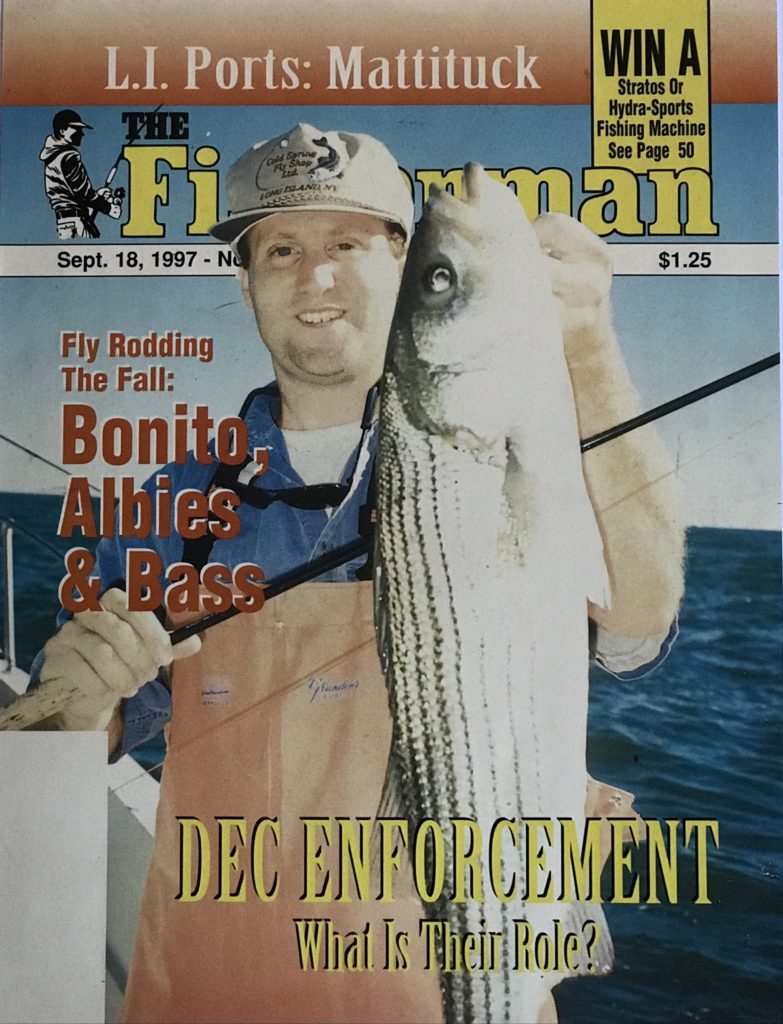

How long does sailing go on in the Northeast? As long as you like, really. Ever hear of ‘frostbiting?’ It’s racing during the winter, usually on small boats and dinghies. I started doing it in high school and stopped during college. I decided it was insane. It’s much better now with better outerwear options, and also because self-rescuing boats are more commonly used than before. I used to race Dyer Dhows, which are still popular in parts of the Northeast including Western Long Island Sound.

The Dyer is basically a bathtub with a sail and fills up with water if you flip it. Positive foam flotation prevents sinking, but a swamped sailor needs rescuing by one of the fleet’s chase boats before considering getting back out. A Laser, on the other hand, can be flipped right back up and back into action with minimal fuss. If one is fast, and stays on the windward rail, they might not even get wet. But, it’s a boat that throws up spray so in any wind, one gets wet just from that. Dry suits are in order here.

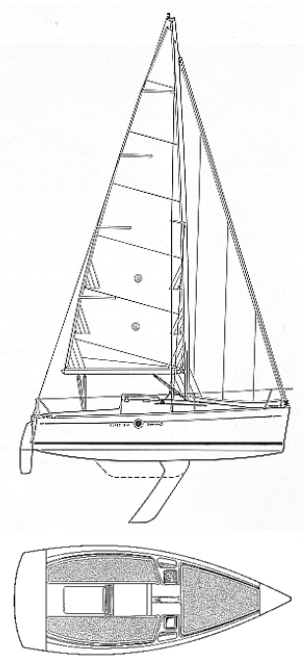

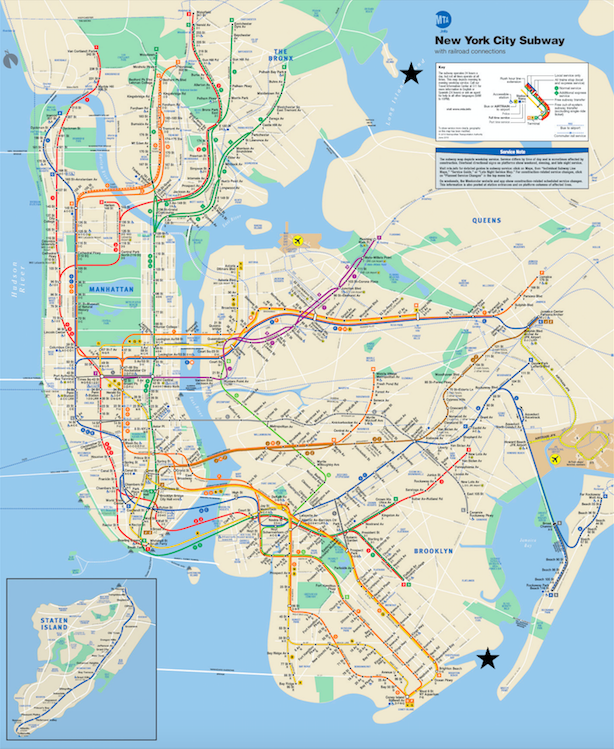

How about bigger boats? Keelboats don’t easily capsize, and they’re drier. Many people extend their seasons well into the fall. At Miramar Yacht Club, which hosts a branch for our school in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, some members keep their boats in all winter and sail from time to time. The Club is open all year, despite launches being hauled out for the winter. The Bay is super calm, so it’s reasonably safe to just row out to one’s boat if weather permits with a life jacket on and others around knowing what you’re up to.

Around 12 years ago, I was living in Greenwich CT. I was in a super kewl and fun/funky apartment complex right on the water, at the end of a peninsula and street, next door to Indian Harbor Yacht Club. Fancy club, and expensive, but a sailors club. The main thing they needed to know before one joined is that you actually were into sailing and active at it. They didn’t care if you had a lowly J/24, as long as you sailed it. They had a frostbiting program in the winter, on Dyer Dhows. And, it was open to non-members. I was very close to just joining that program, as it was happening almost in front of my living room window.

And then, I took a snowboarding lesson. I was a newbie; never did it before. I hadn’t skied since I was a wee boy either, and skiing and snowboarding are very different skills with almost no overlap, so no muscle memory, etc, to dial up. “That’s that with that,” I said. I’d never frostbite again. I wouldn’t have time. Snowboarding is my winter jam. But transitional fall sailing? One of my favorite ways to play!

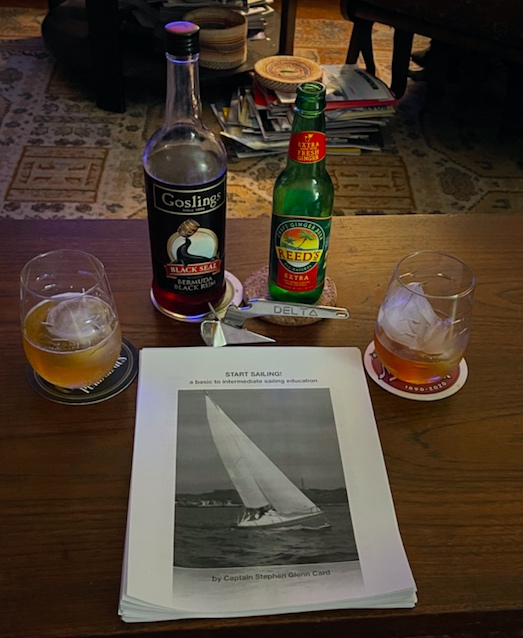

Pro tips for fall sailing:

Dress for fall, but be prepared for summer – or vice versa. You can still easily get sunburned, especially with clearer atmospheric conditions when it’s from the northwest. Bring both a warm hat and a sun hat. And, sunscreen for exposed spots.

Don’t dehydrate. Wind and sun do that, even when it’s cooler. Bring water.

Bring a hot beverage in a thermos or some soup in case you get chilly and need a warm-up.

Do you ski or ride? You can bring those clothes, minus helmet/boots, and you’re in good shape!

If you’re skippering the boat, beware the setting sun. It sneaks up on us early now; we’re conditioned to sail into a sunset that is much later in the summer. Don’t get caught with dimming light and dropping temps when you have a ways to go – especially if the wind picked up from the afternoon sun and hasn’t died down yet.

As well as being a certified sailing instructor with ASA since 1983, when they started, I was a Level I snowboarding instructor with AASI/PSIA for few seasons much more recently. I got certified almost exactly 2 years from when I first got on a snowboard. Not because I was prodigy, but because I had a teaching background and had stubbornly applied myself on a board to get as competent as possible as early as I could. I didn’t even have a goal of teaching – it didn’t enter my mind until I was getting ready for my second full season of snowboarding, and I saw some instructor recruitment info on mountain resort web sites. “You don’t have to be the best skier or rider on the mountain to teach. You have to be good with people, enthusiastic, etc, etc.”

An idea was born. I pursued it. I was hired to teach at Okemo in Ludlow, Vermont, to my great surprise (more on that story in another issue of the Blog Rant.) And, I brought back a lot of instructional cross training and teaching methodology to the Sailing Center. More on that later, too.

I occasionally have free time to give snowboarding lessons, and I always enjoy it. If you’re interested, or know someone who is, shoot me a message by reply to this or from the contact page on our site (in the main menu of every page and post).

Think wind – and snow!