We recently came across this review of our learn-to-sail boat, the Beneteau First 21.0. It’s sometimes called the First 210. Many Europeans call it the Baby Ben.

It’s the smallest sailboat made by the largest (and oldest) sailboat manufacturer in the world. It’s two and a half editions, or generations, or models old depending on how one defines that. Started with the First 21.0; became the First 20. (Boat didn’t shrink.) Then, Beneteau and ASA (American Sailing Association) teamed up to produce a slightly modified version – that’s the “half” to which I refer – called the ASA Trainer or First 22. (Again, the boat didn’t grow.) The chief difference on this one is that they made a smaller cabin and larger cockpit.

But, all versions have these things in common:

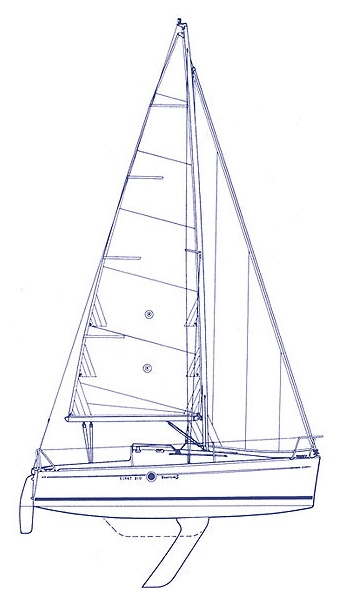

- Hull. (Boat body) The size and shape are the same.

- Keel. (The fin that stops the boat from going sideways and from flipping over.)

- Rudders. (Steering fins.) Yes, plural. There are two.

- Rig. The spars (poles that hold the sails up, out, etc), and basic sailplan, are the same except for the squared-off top of the mainsail on the newer boats.

Bob Perry, a highly esteemed naval architect and author, with a regular column on design in Sailing magazine, penned this article some time ago. Here are his words, and some pics we saw fit to slip in…

Perry on Design: the Beneteau First 21.0.

(Bob’s prose appears below in quotes. Any editorial notes I couldn’t resist are indented in parentheses as I’ve done here.)

“Let’s go small and look at a trailerable boat. This one is from the board of Group Finot and built by Beneteau. It is a very different approach, abandoning tradition and going after speed and convenience with modern design features.

“The benefit of this type of boat is the ability to move easily to exotic or semi-exotic locations for regattas. The 210 will make a great daysailer or a camp-style cruiser. While trailerable sailboats are seldom examples of refined design, the First 210 shows design innovation aimed at sparkling performance and eye appeal. This boat is also unsinkable.

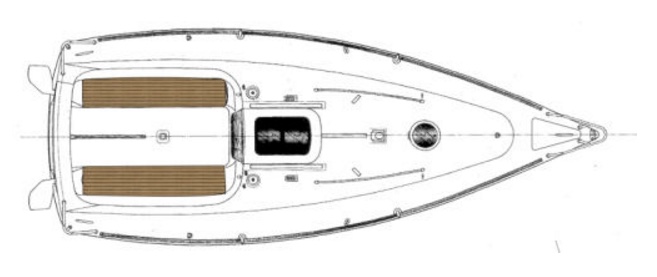

“With an LOA of 21 feet, the First 210 shows a modern, round bilge hull form with a very broad transom to give it dinghylike proportions. Look carefully at the plan view, deck layout or interior. Note the location of maximum beam. In most modern designs the maximum beam is located at or around station six. If you use the same system of establishing stations and break the 210’s DWL into 10 segments, you will find the max beam around station nine! There is even a curious little hook in the deck line right at station nine. The result of this shape is extreme maximization of the small volume available in 21 feet and a wide platform aft to optimize the righting moment effect of crew weight.

(We’ve always called this boat a big dinghy with a keel on it. A dinghy is a sailboat that can flip over and requires the crew’s weight on the rail to hold it down. The Beneteau First 21.0 is very sensitive to crew weight, and reacts immediately to changes – but it won’t flip over if the crew fails to react. That makes it ideal for learning and training.)

“The extremely high-aspect-ratio centerboard (ed. note: it’s a ballasted swing keel, not a centerboard or centerboard keel) is housed in an odd shaped nacelle below the hull for a board-up draft of 2 feet, 3 inches. Almost every appendage is a candidate for “ellipticalization” these days, and I find it interesting that the designers have ended this board in a sharp point. In profile, the rudder looks ridiculously small until you realize that there are in fact two rudders. They are canted outboard at 15 degrees. With this extreme distribution of beam aft a normal rudder would pull almost clear of the water at high degrees of heel. With the two rudders, when the boat is heeled one of the rudders will still be at an effective working angle with the water. This is a slick way of reducing the required draft of the rudders. Note that the draft of the twin rudders is the same as the draft of the board housing. The rudders are linked through the member at the top of the open transom.

(The design was great by itself, but what puts it over the top is the twin rudders. Sailboats lean to the side naturally, as shown in the pic above. The more they lean, however, the less effective their rudder (steering fin) becomes. It loses its bite on the water, so it has to be held to one side to go straight. This creates drag and further reduces its effectiveness. But the twin rudders on the First 21.0, each one angled outward, become straight when the boat heels a normal amount, and when the boat heels too much, the rudder angle isn’t bad. This makes for a forgiving feel that allows students to learn from mistakes rather than be confused or overwhelmed by them. And that makes them better able to sail any boat afterward.)

“There are no overhangs on this little packet. The bow profile shows a hint of concavity to allow some flare into the forward sections. There is also a tiny amount of tumblehome in the midsection with a moderate BWL.

“The shrouds are taken to the deck edge allowing a small jib to be sheeted inside. The mainsheet sheets to a single attachment point on the cockpit sole. All halyards lead aft to jammers within easy reach of the helm. The spar is deck stepped with a hinged step. The interior is a one piece GRP molding with small sink and one burner stove. The portable head is under the V-berth. The small interior space is divided by a trunk that carries that top of the swing keel. A hinged leaf table is attached to this trunk. The four berths are all adult sized.

“On deck, the swim ladder and outboard bracket fit neatly between the twin rudders. The two cockpit lockers contain a space specifically for the outboard fuel tank. The bubblelike desk is striking and set off by a varnished mahogany toerail.

“The First 210 appears to combine careful styling with performance and safety. The general approach to this design is similar to the Mini-Transatlantic Class, but the boat is not as radical in proportions as a true mini-transat racer. Beneteau’s tooling of molded parts is as good as any in the business and their approach to finish and style is perhaps the best in the business. These aspects combine to ensure that the little 210 will be a standout.”

(“Mini-transat” refers to the Mini 6.5 class boat: 6.5 meters, basically the same as the first 21.0. It’s a serious racer. How serious? They are raced singlehanded across the Atlantic – with spinnaker. No shit. They have twin rudders like the Beneteaus. This class is also raced doublehanded for some regattas.)

We love this boat, and while they’re fewer and farther between, and much more expensive to buy than the boats more commonly used in sailing schools (J-24’s and Sonars come to mind), they’re worth it as they just work better for teaching.

“Don’t take our word for it!” Everyone says they have the best boat. But this is the only design ever endorsed for sailing instruction by a national sail training or sailing school organization such as ASA or US Sailing.

Here are a couple of related links…

- Bob Perry’s web site

- Beneteau

- Mini 6.5 class web site (Mini Transat)