A recent shark attack in the Rockaways not far from where we teach you how to sail drives the point home, close to home.

Last Monday evening at 6pm, a woman went in the water off Beach 59th Street in Far Rockaway. She was close to shore, but alone. She screamed, and lifeguards went to help. She’d been bitten by a shark and had a serious wound to her thigh. The New York Post took the sensational route, of course, and also published a lame account of the attack where someone claimed the woman lost approximately 20 pounds of flesh. That would have been her entire thigh and she would have been dead before she could have received treatment. Desapite that being debunked they have not corrected it. They also published close ups of the woman being treated on the beach. Not gory; shows some blood but mostly her being treated and also good samaritans holding her head and hand. Good shot from that perspective, but won’t reprint it here. Go find if you must.

She was brought ashore and a tourniquet was applied. She wound up in Jamaica hospital in serious but stable condition and was expected to not just survive but make a full recovery.

But, that was close! Had she been further out, and/or lifeguards weren’t nearby, she would have had a high risk of dying from loss of blood and shock.

“Yes, but…”

A large, perhaps overwhelming majority, of shark attacks are survived. Most bites are from small sharks and make minor injuries.

It’s scary nonetheless. It was a serious attack. And, there have been a rash of shark bites and all kinds of sightings in Long Island waters in the past year or so. Numbers of sharks seem to be on the rise.

“Yes, but…“

Same diff. Florida is historically the shark attack capital of the world, with a proportionally very large percentage of attacks. Vast majority are minor bites by small sharks feeding on fish.

But but… I don’t WANNA get bit by a shark!

“Yes, but…“

No one does. But the odds against it are insanely in your favor. Compare the number of attacks/bites documented each year to the incalculable number of times people go in the water with the sharks. Total documented attacks? Hovers around 100. (Undocumented attacks probably tip up the number incrementally, but there’s no reason to suspect multiplication is involved).

Also: think about when to get in the water, and when not to, etc…

- Don’t swim at night. Dumb and Dumber didn’t even do that.

- Don’t swim at dawn or dusk. At least as bad.

- Don’t swim in the mid to late afternoon. This is a trigger time for predatory fish to feed, in my lifelong experience as an angler, and it happens to be when many attacks happen (probably more because more people enter the water, but still…)

- Don’t swim alone in waters where sharks might be. Okay; they might be ANYWHERE. So, don’t swim alone where sharks have been seen recently, or where there’s any history of attacks and/or dangerous species being seen.

- Don’t swim out further than others.

- Don’t wear yellow. Divers call it “yum yum yellow.” High-contrast visual trigger.

- Don’t swim when small fish are being chased by birds or other fish, or where where gamefish like tuna have been coming close to shore, even if they’re not there when you go in.

- Don’t swim when there’s any chance you have a cut of any size that could bleed, or if you’re menstruating.

- Don’t swim when the water’s particularly murky.

- Don’t splash around frantically. If snorkeling, no need to smash your fins down on the surface with each kick. Super inefficient anyway; keep fins in water to push water!

Can you get through your natural life without being bitten by a shark if you break some or all of these rules? Yes! You probably won’t get attacked if you break them all.

“Yes, but…“

She did. She swam alone, and shortly before dusk. Don’t know if any of the other rules applied. But, it’s the first documented attack in NYC waters since at least the 1950’s. And, the near-ish attacks on Long Island were all minor.

I consider the fear of attack to be both irrational and rational. I’ve been fascinated by sharks and shark attacks since I was a boy. My dad took me to the South Street Seaport once and, of course, no visit anywhere ends without a stop at the gift shop. I took home a book: Shark: Unpredictable Killer of the Sea, by Thomas Helm. Lost the original but replaced it on Amazon…

Great book. One man’s perspective on sharks, shark fishing, and attacks, with some personal anecdotes. One of them both reinforces and destroys the subtitle. He was stationed in the Pacific during WWII. Somewhere there was a lagoon encapsulated by a fringing reef. His unit was tasked with disposing of outdated grenades. They decided to fish with them. They went out in a rubber raft and started tossing grenades in to stun fish.

BOOM. Up floated many dead fish. BOOM. Again. he-he.

Eventually, sharks came to pick up the scraps. So, why not blow up the sharks? They started tying grenades to fish, pulling the pin, and tossing them so if a shark went to grab it, head blown off. Nasty; wrong. Dumb. But, the author knew it by the time of writing long after and was admitting, not bragging.

Then, they started tossing the fish in immediately after pulling the pin. One shark took the bait and swam toward the raft. Ooopsieee…..

BOOOOOOMMMMM!

Raft flipped and tossed them all in the water – with that much more fish blood in the water.

They all swam back to shore unscathed. So, the sharks didn’t see them as potential prey, despite what must have been some frantic flopping about and plenty of blood in the water already. Should have been… shark bait.

“Yes, but…“ No bites.

Unpredictable. Except, maybe, they’re not unpredictable, indiscriminate killers? Maybe they bite when they’ve rarely mistaken us for normal prey, or in more rare cases, when they’re simply desperate to feed or otherwise thrown off their games?

My own experiences with sharks…

- Seen a few while snorkeling. First was in Australia on the Great Barrier Reef. White tip reef shark. It was lying on the bottom breathing from the current without swimming. The snorkeling guide swam down toward it to spook it into moving. It grudgingly did so, and lazily went in a great circle while no one but I saw it plop down in the same exact spot to resume minding its own biz. Everyone else had swum away. My treat.

- Another time, found a decent sized lemon shark minding its own biz in the Tobago Cays of St. Vincent and the Grenadines. Video’d it with underwater camera (point n shoot in a good case). It spooked and swam further away quickly, then resumed a lazy swim. I got good zoomed in footage. It’s up on our YouTube right now! What I DIDN’T see at the time was the other shark that was what spooked the lemon. THAT scared me! Different species. Never found out what.

- Saw others snorkeling in the BVI. One time, a guy was sitting on the bottom minding its own business. Wasn’t a nurse shark; didn’t match another species I could think of. Started approaching to ID it. Then, I thought better and went away.

- On our most recent BVI trip in spring of 2023, clients were snorkeling off the boat in an anchorage. They got my attention: wanted a ride back in the dinghy. They’d seen a relatively large shark and didn’t want to fool around and find out. At least one of them didn’t. The other, when advised and asked, wanted to stay in and try to see it. Only problem is it had seemingly spooked when the first guy saw it and disappeared. How large? Around the size of the dinghy. 10-11 feet.

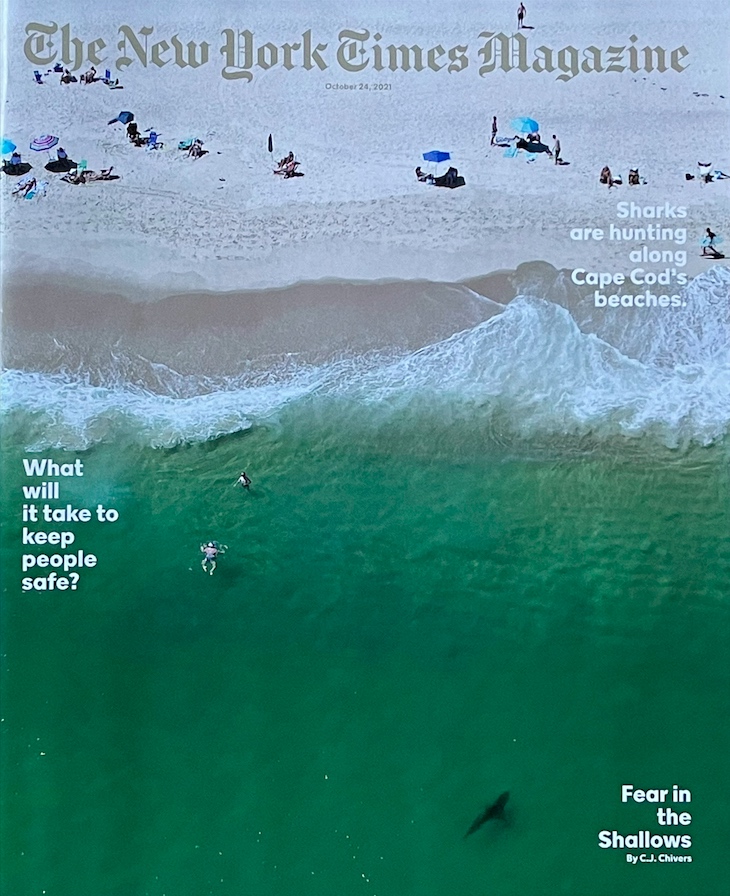

Drones are the new rage, and they reveal how often we’re actually swimming or surfing with dangerous sharks swimming amongst us. Enter Scott Fairchild, whose Insta account is so revealing. And, they’re being used to look for sharks by beach and park patrols to make swimming even safer.

And now for a few words and images from someone other than me!

Great montage in Scott Fairchild’s Instagram account…

https://www.instagram.com/p/CsbfJ5Pucnf/

Article in NY Times about the Rockaway attack with good perspective and info about drone patrols…

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/13/nyregion/rockaway-beach-shark-bite.html