More about the spate of attacks at Cape Cod and other New England spots over the last decade. No, no sailing or cruising or yacht or such involved here. It’s just something we predicted awhile ago.

A student of ours from quite awhile ago, Tyler Hicks, did the still photography for the article we link to here, coincidentally. We hope he’s kept up with his sailing!

Why am I writing about shark attacks on a Sailing Club/School site? Because I can. This is our Blog Rant section and I do what I want. But, there’s relevance and it’s more than the fact that one of our students took some photos. Everywhere we travel for our destination Sailing Vacation courses, we snorkel and/or swim. And, anywhere people choose to swim, there can be sharks.

First thing to know: it’s safe! True, every year around the world there are a number of shark attacks and a few fatalities. But compared to the number of times humans enter the water each year, it’s a ridiculously rare occurrence for anyone to be bitten, far less killed. Even in the places that statistically have more attacks than others, it’s extremely rare. That’s why people continue to go surfing, snorkeling and diving in those areas. In fact, most people who survive shark attacks (the overwhelming majority do) get back on the horse, so to speak. They go back in the water.

“Just when you thought it was safe to go back in the water…”

the crap they used to hype JAWS 2

Another reason I choose to write about it here is it’s something I know something about. I’ve been fascinated with sharks since I was a little boy. One day, my father took me to the South Street Seaport. When we were done exploring the waterfront and vessels, we ducked into the gift shop. I wound up walkIng out with a book called “Shark: Unpredictable Killer of the Sea.” Author: Thomas Helm. I read it. I watched documentaries. I read other books and articles. I read statistics via the International Shark Attack File. I went fishing… sometimes for sharks. I snorkeled a lot. On rare occasions, I would see a shark.

And, yes – I saw sharks on our trips! They weren’t “man-eaters” on the prowl to eat anything they saw, or tear up hapless swimmers for sport and then spit them out so they could chomp more chumps. They were minding their own business, and had no business with us.

Now, about those great whites on Cape Cod…

They’ve been there for awhile. They started showing up near shore and even in the surf. As the article discusses, the sharks were almost certainly responding to increased stocks of gray seals that were migrating seasonally to the Cape. Fish follow food, as do marine mammals. All this was a sign of a healthy ecosystem that had been recovering from overfishing and pollution. Well before there was any discussion of great white sharks near swimmers and surfers on the Cape, light tackle sport fishing enthusiasts (another hat I’ve worn on and off most of my life) became aware of striped bass and bluefish coming in closer to shore more consistently in the summer and fall on the flats of the Cape, and sight-feeding. One photo in the article shows a great white with a striped bass in its mouth.

When the sharks become public knowledge, and attacks began, a cottage industry sprung up with shark paraphernalia and such. Also, the parks department put someone in charge of trying to ensure some balance of public safety awareness and preparedness on the one hand, and allowing people to continue getting in the water on the other. That’s been evolving, especially after something that I’d predicted for years finally happened: someone was killed by a shark in the Cape Cod surf.

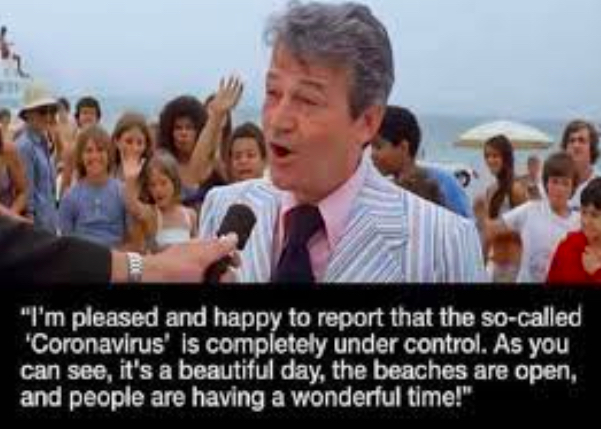

As people were continuing to swim and surf, and the sharks were arriving in more numbers, as well as slowly growing as they returned season after season, it was inevitable. If nothing changes, then inevitably there will be the occasional attack and possibly a fatality. But, what would change? Can’t kill the sharks. Can’t kill their food supply. Can’t stop the sharks from swimming where they will. Can we stop people from going in the water? Cue up the scene from the original Jaws, which became a popular meme during the pandemic:

Some residents in Cape Cod think that locals should be able to decide if and how much to cull the seal and shark population to protect those who play in the water and therefore the economy. Others think that’s ‘playing god.’ My takeaway? I’ve never been attacked by a shark, nor known anyone who has. However, those who survive attacks – and those who survive those taken from us by shark attacks – mostly, if not vastly, side with the sharks. They believe that we’re entering sharks’ territory, at our own slight risk, and that sharks are just doing their thing: going about their simple lives surviving. Therefore, leave them alone.

I happen to agree.

“We’re dressing up like their food, and swimming among their food, and we still hardly ever fool them. People will drive down to the beach while they are texting and then they worry about getting bit by a shark?”

Chris Fischer, founder of the non-profit research organization OCEARCH.

So, what happened on the Cape? I’ll let you read the article as it’s a good one. It covers attacks on the Cape, as well as one along the coast in the Bay and one up in Maine in 2020. Two out of the five encounters were fatal. Strangely, despite referencing “Jaws” appropriately on several occasions, the article doesn’t point out that the book by Peter Benchley and the subsequent movie (and sequels) were inspired by real events. What were they?

“12 Days of Terror,” according to one author. In the summer of 1916, there were five shark attacks in New Jersey in the span of 12 days. All but one were fatal. Three of them happened basically back to back in the same one small body of water, Raritan Creek. The other two, which preceded these, were separate attacks at different beaches along the NJ coast. There’s been a lot of conjecture over the century since those attacks about what happened. However, one fact remains: a juvenile great white shark of around 7.5 feet was caught in Raritan Bay shortly after the last attack, and it had human remains in it’s digestive tract, including some positively identified as belonging to one of the attack victims.

After it was caught, the attacks stopped.

Two of those attacks were likely survivable had proper 1st aid been administered and if infrastructure and logistics existed for rapid transport to a trauma facility. Two were not. The fifth and final attack was when a group of kids swimming were warned that there had been an attack further down the creek, and they all scrambled out. The last boy climbing out was struck on the leg by a shark and badly wounded. It’s not clear whether his leg was amputated to save his life; reports conflict. But, he survived.

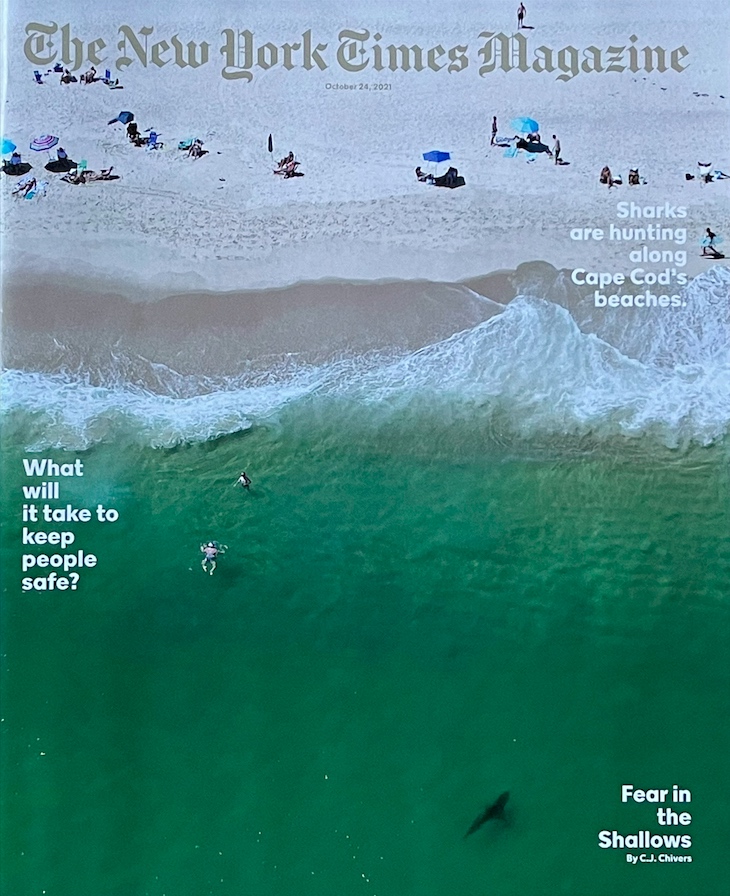

What about drones?

Obviously, the cover shot for the Times piece is spectacular and the work of a drone. As the piece discusses, drones might be the future of preventative measures along beaches. My takeaway? We’re seeing more and more images like this, where people are in the water blissfully unaware that sharks are quite close by. In many if not most cases, this peaceful coexistence had always been the case. Now, drones are letting us see it for ourselves. That’s not the case on the Cape, where the increase in shark numbers is well documented. But, I wouldn’t be surprised if we keep seeing pics and clips from drones that show how often people are in close proximity to “man-eating” great whites that clearly know the people are there – and clearly don’t care. Until they do, of course, but the drones might very well get people out of the water in advance and reduce the already very slight risk that a shark might bite someone in the water.

And, finally… here’s a link to the entire and very worthwhile article!..

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/10/20/magazine/sharks-cape-cod.html