As yet another day dawned recently with the doom and gloom of thunderstorms in the forecast, I decided we were overdue to revisit the issue of predicting and avoiding them. This summer has seen more than its share.

By now, most of you have probably heard about the ‘duck’ boat that sank in a severe thunderstorm in Missouri, killing 17 of the 29 souls on board. As is typical, we don’t yet have a complete picture of what happened. Two questions have arisen:

- Are these craft inherently unsafe?

- Did the operator recklessly proceed in the face of approaching storms?

We’ll add a third: how do people manage to get caught in these storms, especially licensed professionals?

“On Thursday, the area around Branson was placed under a severe thunderstorm warning shortly after 6:30 p.m. local, about half an hour before the boat sank. Authorities received the first 911 call about the sinking at 7:09 p.m., according to the Stone County sheriff.”

CNN; link at bottom.

‘Yet the duck boat owned by Ripley Entertainment entered Table Rock Lake 23 minutes after the National Weather Service issued a severe thunderstorm warning for the area. That alert included Table Rock Lake and warned of winds in excess of 60 mph. In reality, winds on the lake hit 73 mph with waves of more than 3 feet. (ed. note: the craft was only allowed to operate in winds up to 35 knots by US Coast Guard inspection and certification.)

When the boat started its water tour at 6:55 p.m. on July 19 the lake appeared calm. Around that time, emergency crews in Taney County began responding to calls about toppled trees and downed power lines caused by the storm.

Just after 7 p.m., whitecaps were visible on the water and winds increased, according to an initial report released by the National Transportation Safety Board on Friday. Less than a minute later, the captain of the Ride the Ducks boat made a comment about the storm, the NTSB report said, without any further explanation.

By 7:09 p.m., the first 911 call about the struggling boat came in.’

-Kansas City Star, link at bottom.

The NTSB and the Coast Guard are investigating whether criminal charges ought to be brought against anyone, which means there’s significant doubt about the wisdom of the tour craft having left shore in the first place, or suspicion of actual wrongdoing. That’s pretty serious.

So, how could it have happened?

I don’t know for sure; I wasn’t there. Reports are sketchy, except for the facts that the entire area had been under a thunderstorm watch for awhile, which was elevated to a warning of severe thunderstorms. If the operators were watching the weather events unfold on their smart phone/s in real time, they should have seen it coming to the area and not left port. Unless, of course, the main mass appeared to be missing by a safe distance and this was a ‘pop-up’ storm. But it doesn’t appear to have been from the available reports and evidence, especially its strength. Pop-ups tend to be smaller, quicker, and less intense.

If the pros can get caught off guard, what chance do all y’all have as recreational boaters?

The answer is: the same as they do. It’s not rocket science. We can all see what’s happening and play it safe. Here’s what I use… a site called CT Precip, with a URL of www.pluff.com…

- Green: rain.

- Yellow: moderate rain.

- Red: heavy, and probably a real thunderstorm complete with lightning.

- Purple: game over.

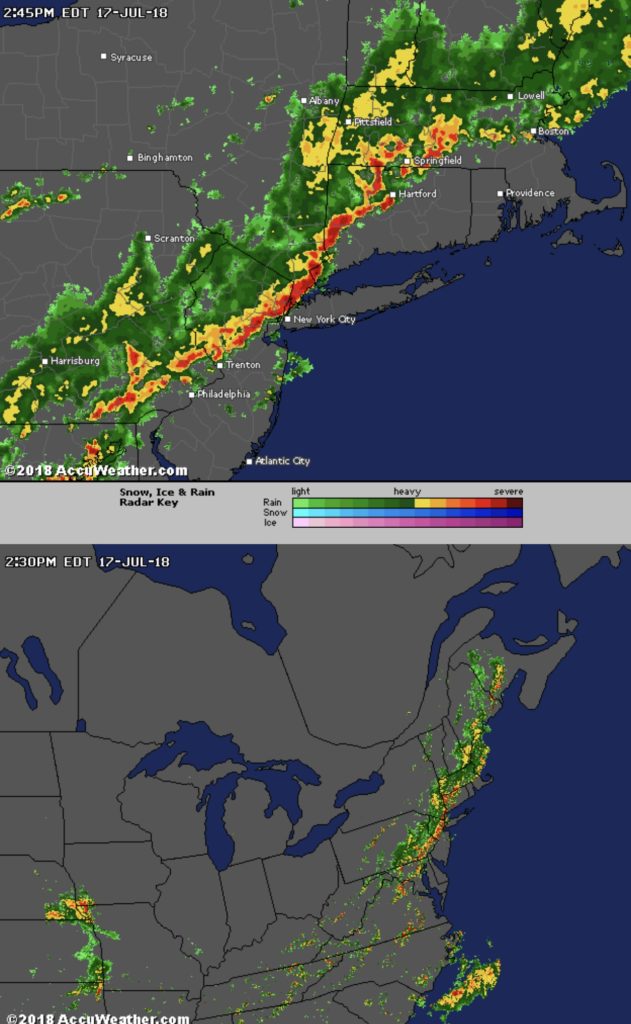

Weather radar is easy enough for the average boater to have a sense of what’s coming. It’s accessible to all of us on our smart phones, meaning we’re stupid when we don’t look at them for this purpose. When heavy thunderstorm activity is moving our way, it’s obvious. The exact timing isn’t obvious, and sometimes it’s not completely clear if our exact location will be hit. But that’s splitting hairs – even for many pros.

Weather Radar apps tend to show about an hour and a half of motion of whatever is out there (or not on clear days). If the system has moved consistently for the past hour and a half, then one can see where it’s going next. If it’s ‘brewing,’ or constantly changing, the picture might not be as clear, but the direction and rate of travel might still be. Any ambiguity? Don’t go out on the water – or get off it! If that’s no longer possible, then at least one can make preparations before it hits.

One of the most severe events is a line squall. It’s when a clearly delineated band of weather that’s long and narrow is moving consistently and rapidly. It’s sometimes referred to as a ‘derecho.’ In the northeast, we get them moving west to east, or right. (‘Derecha’ is Spanish for ‘right,’ so I’m assuming there’s something going on here.) Actually, our derechos can span a huge tract from the Mid-Atlantic up through the Northeast. When they’re coming, you know it.

The worst storm we experienced in recent years was worse than all this. Much, much worse. We didn’t screen capture it at the time. It was a large mass that was moving south from upstate NY, and it was going to engulf all of NYC, Lower Westchester, Northern NJ, Nassau County LI, and parts of SW Connecticut. At the same time. We closed up shop and were safely eating lunch ashore when it hit. We know half a dozen sailors who got caught in it – and all took knockdowns, but survived. Unfortunately, at a competing sailing school, someone didn’t. A Day 1 class was actually in progress, on a boat without lifelines. No one aboard was wearing a PFD (life jacket). All wound up in the water; one never made it back.

And what did everyone who got caught in it say? “You couldn’t see it coming.” That’s what they all say.

But they’re wrong. Dead wrong. The Radar reveals all. That’s how I managed to stay out of trouble, after being on heightened alert from the earlier forecast (which was for severe thunderstorms that had already caused significant damage further north).

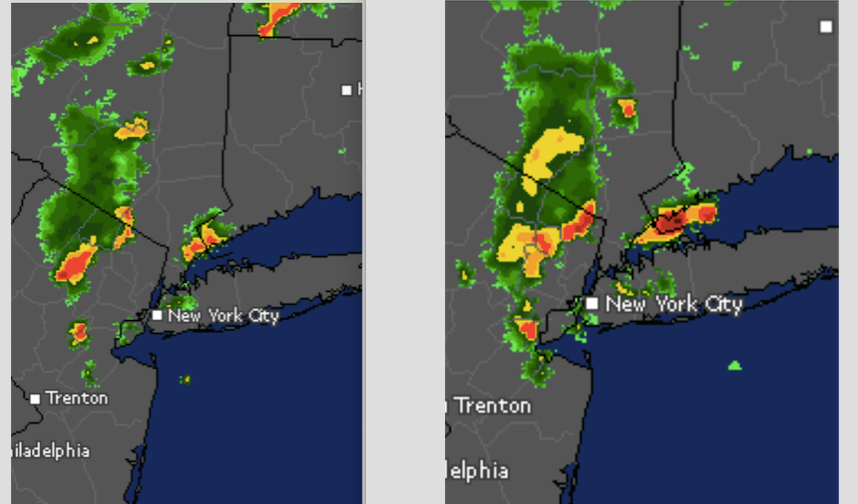

Heres’ a pair of Radar observations 20 minutes apart. These were taken this season when a slow moving and brewing cell developed. We stayed close, then got off the water…

Smaller area; harder to be sure what would happen. In that case, just call it quits. That’s what we did. And we stayed safe and dry.

So, the next time you’re out and about, be sure you’re ready to check the radar first. The marine and general weather forecasts will let you know whether to go to the water and get on it. The Radar will tell you whether to stay there. They’re interrelated. Don’t leave home without a way of checking both!

And now, those links I promised…

CNN, https://www.cnn.com/2018/07/23/us/missouri-duck-boat-investigation/index.html

Kansas City Star, https://www.kansascity.com/news/state/missouri/article215930835.html

One thought on “Dead Duck Boats and Ducking Thunderstorms”