It’s not going well for the formerly very reputable Clipper Round the World Race. So far in this season’s event, one vessel was totaled when it ran aground, and another lost a crew member overboard who tragically didn’t survive.

In the 2015/16 race, one vessel suffered two separate fatalities – a trauma injury aboard, and an overboard fatality.

So, what’s going on? Is it like the Greek ferry system – enough volume that there will be inevitable accidents – or is something rotten here?

Time will tell, we suppose, but in the meantime, the British Government weighed in after the dual tragedy of the 2015 race, and issued some findings. But first, some background for context…

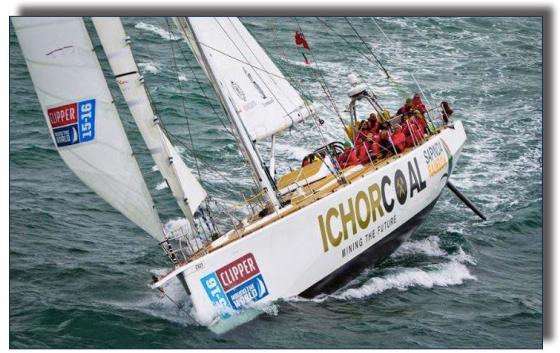

The Clipper Race is a multi-leg, circumnavigation event with large one-design (basically identical) racing yachts. What sets it apart from the Volvo Ocean Race and other events is the amateur status of the crews. There’s a professional skipper on each vessel, with crew who are not. These amateurs, who pay to play, sign on for anywhere from one leg to the entire event, and go through formal training specific to and run by the event organizers before participating.

This is the 11th running of the Race. It’s had a clean history until 2015. This is trans oceanic racing, and it’s sometimes grueling. Stuff is going to happen from time to time. But, casualties are not expected even for serious offshore racing. Fatalities do occur, but are rare and usually confined to very severe weather events. So, what’s going wrong here?

Perhaps the British Government has some insights. Their Marine Accident Investigation Board convened an inquiry after the 2014 deaths. Their core conclusion? Perhaps one ‘pro’ skipper isn’t enough:

‘While a single employee on board a commercial yacht may provide sufficient company oversight in many circumstances, the special nature of the Clipper Round the World Yacht Race places a huge responsibility on one person to ensure the safety of the yacht and its crew at all times.

‘Therefore, in addition to acknowledging the completed and ongoing actions taken following the two accidents featured in this report, I am recommending Clipper Ventures plc review and modify its onboard manning policy and shore-based management procedures so that Clipper yacht skippers are effectively supported and, where appropriate, challenged to ensure that safe working practices are maintained continuously on board. In particular, consideration should be given to the merits of manning each yacht with a second employee or contracted ‘seafarer’ with appropriate competence and a duty to take reasonable care for the health and safety of other persons on board.’

-Steve Clinch, Chief Inspector of Maritime Accidents, in his Foreword to the “Report on the investigations of two fatal accidents on board the UK registered yacht CV21 122nm west of Porto, Portugal on 4 September 2015 and mid-Pacific Ocean (39° 05.3N, 160° 21.5E) on 1 April 2016”

The report is extensive, and you can read as little or as much as you like on your own here. The quote above is worth noting on its own due to the nature of the event.

Here’s another:

“Although MOB drills had been briefed on board CV21, no practical MOB drills were completed with the crew for the Race leg together, an omission in common with other Clipper yachts.”

-from the synopses of the report.

Several of our own students at New York Sailing Center have gone on to do trans oceanic voyages, including one who participated in the Clipper Race and was himself washed overboard in rough weather but remained tethered to the yacht. Sarah Young, the overboard victim in the 2015 race, was not tethered to the vessel. Simon Speirs, who perished in the current race, was tethered, but the gear failed. Both sailors were lost in gale or near-gale force winds. We sail in those sometimes in Long Island Sound with advanced classes, but it’s not the same. Winds in the 30’s that are ‘offshore,’ or blowing from land to sea, don’t create large waves that can make the vessel pitch dramatically and also break over the boat and literally pick people up and deposit them wherever.

Sarah Young’s failure to clip on in those conditions was an anomaly, but the gear failure that allowed Simon Spiers to be separated from the boat was a testament to the forces involved – and not a totally freak occurrence. In the real rough stuff, it’s been known to happen before in offshore circles.

Given the amateur nature of the Clipper Race crew make up, perhaps there should be rules governing when people may go forward on the boats in rough weather. In this case, it was to do a headsail change. That’s inherently dangerous in large seas. If the necessity to do this is due to the choice of rigging, maybe it needs to be changed. If it’s due to the size of headsails that are allowed, perhaps those should be limited. Perhaps once seas kick up to a certain height that suggests worse to come, but is reasonable at the time, that ought to be the point at which a proactive headsail change is done if the equipment can’t be altered to accommodate staying in the cockpit. If modern furling systems aren’t up to the task of open ocean racing, then that’s the next best thing.

The Clipper yachts use ‘cutter’ rigs, where there are two places to have sails forward on the vessel. That should allow very good flexibility in sail plan choice, and reduce the time spent forward dealing with sails – or potentially eliminate it. I don’t claim to be an expert in open ocean sailing, but if there’s a pattern developing with safety issues in this event, then let’s keep everyone safer – and still on an even keel – with gear changes and strict safety rules that mitigate this risk.

Here’s a link to the UK’s accident report, and also the Clipper Race site…

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/58ee0b5040f0b606e7000166/MAIBInvReport07_2017.pdf